What's this about?

The last two articles I've written for the blog were part of the Particle Physics series. While this article relates to more general physics, we will still discuss conservation laws related to the Standard Model by the end. So if you are interested in particle physics, I hope you'll find this a good read!

Fair warning: I do not claim to be an expert on this topic. What I am discussing here is what I have come to understand regarding symmetries and conservation laws through my own personal research into the topic and my studies at university.

Intro

When I say symmetries, you may think of, for instance, a square, and you would be correct! A square is symmetric about 4 different axes: a horizontal one through its centre, a vertical one also through its centre and its two diagonals. Another simple geometric figure that exhibits symmetry is the circle. A circle is symmetric about an infinite number of axes, because you can draw any line that goes through the circle's centre and it would be symmetric about it. And since we can draw an infinite number of lines through a circle's centre, it must have an infinite number of axes of symmetry. These are demonstrated here:

This image shows the four reflection axes of symmetry of a square. This means that if the square is reflected across any of these lines, the end result is the same as the starting square.

The reflection axes of symmetry of a circle. Again, if the circle is reflected across any of these lines, the end result is the same as the starting circle.

Image from brittsmathematicalblog

Defining Symmetry

We can formally define symmetry in multiple ways. Firstly, let's think of a definition that relates to our everyday life. We can say that symmetry relates to a sense of balance in an object. Take the example of the square above, we can intuitively tell that it is symmetrical around the vertical axis because the line divides it into two equal and mirrored pieces. The same happens with the circle.

To be more formal, in mathematics, a symmetry can be defined as the quality of being invariant under a transformation. A transformation in this case can be any sort of mathematical operation that we can apply to a system (or figure). This can be anything like reflection, rotation or scaling.

In Physics...

This also applies to physics in a similar way. In physics, a symmetry is generalised to esentially mean an invariance in a quantity, under any sort of transformation. This is acutally cooler than it sounds, in my opinion, and I'll demonstrate this soon. This transformation can be anything from the movement of a falling box to a subatomic particle decaying into other particles, and more. The quantity here can be things like energy and momentum, which, if you have done some sort of high school level physics course, you will have come across.

Conservation

You would also have been taught that such quantites are "conserved". This is exactly what the symmetries here are referring to! A conservation in a quantity implies invariance, which means the total amount of a quantity in a system does not change. Essentially, when we talk about a symmetry in physics, we are talking about a conservation law such as the law of conservation of energy.

Example: conservation of energy

The Law of Conservation of Energy

The total energy of a system (or some object) is constant as time progresses. Energy cannot be created or destroyed in the system, rather it can be transformaed from one form to another.

Consider an object, a box, that is dropped from a cliff and then falls freely towards the Earth. Now, at the moment that this box was dropped, it will have a certain amount of potential energy that is related to its mass and the height of the cliff. At this point, the box has no kinetic energy because it has not started moving yet. At any point during the fall, its total energy is given by the sum of the potential and kinetic energies of the box.

You let the box go and it starts accelerating towards the Earth. As it gains velocity, its kinetic energy must increase. But where is this energy coming from? The law of conservation of energy tells us that this energy cannot be simply coming from outside of the box, i.e. created out of nowhere. But wait! Because the potential energy of the box is directly related to its height (that is, how far away it is from the ground), then surely as the box falls, it is losing potential energy. So where does this energy go? The law of conservation of energy tells us it cannot be simply going outside of the box, i.e. destroyed.

It is easy to see what is happening at this point. The potential energy that the box loses while it falls is transformed into the kinetic energy which it gains causing its velocity to increase (indirectly; the velocity is actually increasing due to the acceleration caused by gravity). So indeed the total energy of the box (the sum of the potential and kinetic energies) remains the same as it was in the beginning.

Consider the box after it has fallen half the height of the cliff (that is, it is now halfway to the ground). Its height from the ground has been halved and as such, so did its potential energy. So now the potential energy is half its initial value with the other half having been transformed into kinetic energy. If we add this up (to get the total energy), we get the potential energy of the box when it was at the top of the cliff which was, indeed, the total energy of the box as its starting position.

So what just happened? The box is moving, yet its total energy is staying the same. This actually should not be surprising to you. It makes sense that energy stays the same in this way. But what is this? The box is moving (undergoing a transformation), and a quantity that it has is conserved. What does this sound like? This is a symmetry in energy. An invariance!

The total energy of the box does not change as it undergoes the transformation of movement!

This was a fairly simple example that demonstrates the concept of a symmetry in physics using something that we experience in everyday life. We will also be looking at symmetries in the quantum world in the rest of this article. I will assume that you have a basic knowledge of the Standard Model up to what I have previously discussed in this blog in part 1 of the Particle Physics series: Why is the Standard Model so cool?. If you would like to read this first and come back, you can find it here. For now, let's have a short break and talk about symmetries in nature.

Interlude: A break from the physics

On a more general note, let's take a moment to look at symmetries all around us. For the purpose of this, I will generally be talking about visual symmetries, like the example of the square and the circle described above.

This is a starfish. In addition to the obvious reflection symmetry about a vertical axis down the middle, if you look closely, you'll realise that the shape of the starfish has rotational symmetry, that is if you rotate the starfish by certain angle, then it will still look the same. The angles of rotation are determined by the angles between its arms. Rotate it clockwise such that another arm takes the place of the top arm, and it will look the same!

This is an example of symmetry in our bodies. In this arrangement, our hands mirror each other and so have reflection symmetry.

Image from suryambika.blogspot.com

This image shows symmetry in architecture.

This is an iteresting one! The pattern show here on an aloe vera plant occurs due to the leaves expanding based on the golden ratio, a mathematical ratio that seems to occur throughout nature. This causes it to have rotational symmetry.

In addition to the symmetry we find in nature, we tend to build structures that exhibit symmetrical properties. It is almost like we intrinsically find something beautiful about symmetry. Of course, beauty is in the eye of the beholder!

To wrap up this section, I'd like to share a short personal story about something I used to do when I was younger. If you're here just for the physics, Feel free to skip this section. Otherwise, read on!

I recall this habit I used to have when I was much younger where I would go into the kitchen where my mum would keep cartons of eggs. Obviously, the arrangement of eggs in a full carton is symmetric. The problem (to me) arose when eggs would be used for cooking, leaving the remaining arrangement "incorrect". So I would always go up to the carton and start rearranging the eggs until I reach some sort of reflection symmetry. I would then still keep rearranging to see if I could get reflection about a different axis, or possibly if I could it get a completely different shape but still exhibiting reflection symmetry. My mum would sometimes see this and ask me about it and why I do it. My reply would always be "it must be symmetric!".

I suppose you could consider this an obsessive habit, but I enjoyed doing it. I think I just always saw a beauty in that symmetry. While it probably did not have anything to do with inspiring me to pursue physics, it is still a very vivid memory to me! But anyways, let's get back to the physics!

Symmetries in the quantum world

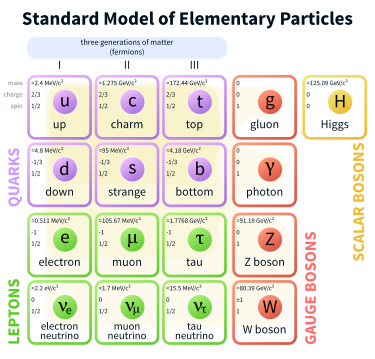

In part 1 of the Particle Physics series, we discussed the different particles that make up the universe. These were mainly the quarks, the leptons and the bosons. There are shown here in the Standard Model:

The Standard Model of Particle Physics

Image from Wikipedia

We discussed how quarks have a unique quark flavour (upness, downness, etc) and how leptons have lepton numbers (electron lepton number, muon lepton number, etc). These quantum numbers are intrinsic properties that these particles have. They essentially define the particle. An up quark has an upness of 1. Both the muon and the muon neutrino have a muon lepton number of 1. An antibottom quark has a bottomness of -1, and so on. These properties are summed up in these tables:

| Upness | Downness | Charm | Strangeness | Topness | Bottomness | Charge | |

| Up Quark | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2/3 |

| Down Quark | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | -1/3 |

| Charm Quark | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2/3 |

| Strange Quark | 0 | 0 | 0 | -1 | 0 | 0 | -1/3 |

| Top Quark | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2/3 |

| Bottom Quark | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | -1/3 |

Quark flavour numbers. Recall that the antiquarks corresponding to the quarks shown above would have exactly the opposite set of properties. An antiup quark would have an upness of -1 and a charge of -2/3. An antistrange quark would have a strangeness of +1 and a charge of +1/3.

| Electron Lepton Number | Muon Lepton Number | Tau Lepton Number | Charge | |

| Electron | 1 | 0 | 0 | -1 |

| Electron Neutrino | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Muon | 0 | 1 | 0 | -1 |

| Muon Neutrino | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Tau | 0 | 0 | 1 | -1 |

| Tau Neutrino | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

Lepton numbers. Again recall that the antileptons would have the opposite values for these properties. An antitau would have a tau lepton number of -1 and charge of +1, and so on.

The leptons and the quarks (collectively called the fermions) make up all the matter that we can see and touch. The bosons (to the right of the SM) represent the forces through which the fermions interact with one another. Recall the four fundamental forces of nature:

- The Electromagnetic Force: mediated by the Photon

- The Gravitational Force: mediated by the Graviton (hypothesised)

- The Strong Nuclear Force: mediated by the Gluon

- The Weak Nuclear Force: mediated by the W and Z Bosons

Now, remember also from the above that a symmetry is essentially a conservation law in physics. At least, a result of a symmetry is a conservation law. That is, every symmetry corresponds to a conservation law (this is known more formally as Noether's theorem).

There is a conservation law that applies for each one of these quantum numbers. However, to apply a conservation law here, we have to know what constitutes a "transformation" as before. In the quantum world, we can consider a transformation to be an interaction of one or more particles through one of the fundamental forces described above.

For example...

An interaction could be, for instance, an electron absorbing a photon of a certain energy, raising the electron's energy level. This occurs through the electromagnetic interaction. Here we can say the laws of conservation of electron lepton number, charge and energy apply. Of course, energy here is not a quantum number (it is quantised though) but energy is always conserved! Let's look at electron lepton number and charge. We can consider an interaction to have a bunch of "input" particles and a bunch of "output" particles (in reality, it is slightly more complicated that this, but this will be further explained in a future blog post). In this case the input particles are the electron and the photon. There is only one output particle and that is the electron (which is now at a higher energy level). The photon is neutrally charged and since it is not a lepton, it has no lepton number. The electron (in the input) has a charge of -1 and an electron lepton number of +1. So the total charge of the left hand side of the interaction is -1 and the total electron lepton number is +1. On the other hand, only an electron is in the output particles of the interaction, which of course also has a charge of -1 and an electron lepton number of +1. So the total charge of the right hand side of the interaction is -1 and the total electron lepton number is +1. These properties of the system did not change. The system has symmetry with respect to those quantum numbers!

This is only a simple example regarding a very simple fundamental interaction that can occur in nature. I will be writing an article exploring more complex interactions than this some time in the near future.

Some forces break the law

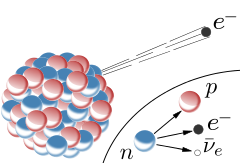

As mentioned before, each of those quantum number has an associated conservation law that is a result of a symmetry. However not all the fundamental interactions preserve that symmetry. This is very important to consider. Most importantly, it is important to realise that the weak nuclear does not conserve quark flavour numbers. As a matter of fact, this is essentially how beta decay occurs:

Beta decay. The neutron (which consists of an up quark and two down quarks) becomes a proton (which consists of two up quarks and a down quark), breaking the laws of conservation of upness and downness. This can only happen through the weak force where the neutron also emits a W- boson (not shown here) which then decays into the electron and the antielectron neutrino shown in the diagram.

Image from Wikipedia

Important symmetries in quantum physics

Generally, there are three important symmetries which essentially give rise to these conservation laws. Those are C-symmetry (charge), P-symmetry (parity, or more simply space) and T-symmetry (time). These are tricky to describe in simple terms so bear with me.

In this context, when I, for instance, say that a transformation (or interaction) shows C-symmetry, it means that if the "input" and "output" particles had their charges flipped (became their antiparticles), then the interaction would still be valid. This will hopefully be clearer when we consider the symmetries individually.

C-symmetry: charge-conjugation symmetry

If a transformation obeys C-symmetry, this simply means that if the same transformation was to be applied to the antiparticles of all particles involved, then the transformation, essentially, would still make sense. This involves charge-conjugation of particles. This simply means that the charges of all particles are flipped (in addition to their quark flavours and lepton numbers). This symmetry is obeyed by the electromagnetic, the strong nuclear and the gravitational forces but is violated by the weak nuclear force.

This means that the beta decay interaction shown above would not be possible if we conjugate the charges of the particles involved. This comes down to the nature of the weak force and because of another property of the particles involved called helicity, but this is beyond the scope of this article.

P-symmetry: parity symmetry

Parity symmetry describes whether a transformation is the same if the space was "flipped", or more simply, mirrored. Because we have not discussed the parity quantum number yet, there is not much to say about parity conservation here. However, suffice it to say that a transformation (or interaction) obeys parity conservation if it would look the same had it been performed in a mirror image universe! Like C-symmetry, the weak interaction does not conform to P-symmetry, that is, it does not conserve the parity quantum number.

Invariance under CP?

Notice that we can combine symmetries! For example, here, we can say a transformation is CP invariant if it would be the same after flipping the charge of particles and mirroring space.

In the mid 20th century, physicists were hoping this would solve the weak force symmetry problem. However, this turned out not to be the case! The weak force (in some cases) also violated CP-symmetry. This posed a problem because we are trying to find some symmetry which would result in the conservation of all properties of the particles involved which would mean all the laws of physics are the same under that symmetry. There is one more symmetry that we are going to consider, which when combined with C- and P-symmetry indeed results in such a symmetry.

T-symmetry: time reversal symmetry

Sadly, there is no time travel here! Time reversal symmetry refers to whether a transformation could still apply if time moved the other direction, that is, backwards. This may be a little difficult to grasp at first. A way I like to think of it is by asking the question: would an interaction happen the other way around? For instance, in the beta decay interaction shown above, would the proton be able to combine with the electron and the antielectron neutrino to form the neutron again?

Most systems are asymmetric with respect to time reversal. This is due to the second law of thermodynamics (entropy always either remains constant or increases), which is beyond the scope of this article. Suffice it to say, most interactions break T-symmetry.

CPT to the rescue!

Only a combination of these symmetries would give us a framework underwhich the laws of physics are truly invariant. This forms the basis of the CPT theorem.

CPT Theorem

The laws of physics are the same under charge conjugation, space mirroring and time reversal.

This is essentially stating that all four fundamental forces exhibit a symmetry if:

- particles are turned into their antiparticles

- space is mirrored (parity of particles is flipped)

- time is reversed ("output" and "input" particles are swapped)

Conclusion

This has been a lengthy article! I hope you've found it entertaining to read and informative.

What did we cover?

We started by looking at visual symmetries of squares and circles, then at energy conservation and finished by seeing how reversing time affects fundamental particle interactions, so I would say we have certainly covered a lot! I hope I was able to convey to you some of the beauty that we can find deep down in the quantum world, which I personally find very cool.

What's next?

I am still unsure about the topic about which to write next. I will most likely either be writing about particle interactions or Einstein's famous formula E=mc2. I hope you will be back here to read it in about a week when it's live!

Closing remarks

Thank you for taking the time to read this. Again, I hope you've enjoyed it! Please feel free to contact me about anything regarding this article; I'd love to hear what you think! One last thing, I have recently added the ability for readers to subscribe to the blog such that they are informed when new articles are posted. If you found this article enjoyable, please consider subscribing here. Thanks!

Related

You may also be interested in:

Observers affecting reality? The Double Slit Experiment

Particle Physics, Part 1: Why is the Standard Model so cool?